Takatāpui

Key points:

An identity that encompasses all Māori who have various genders and sexualities.

Gender and sexuality variances existed pre-colonisation and were even part of important oral traditions and stories such as the legend of Tutanekai and Hinemoa.

Takatāpui straddle 2 important minority groups which could foster more societal bigotry, promote further negative health experiences, and overall lead to worse health outcomes.

Promotion of the use of Māori health frameworks may help to provide more culturally appropriate care.

Things we can we do as health professionals:

Acknowledge and enhance their takātapui identity.

Upskill in both LGBTQIA+ and Māori health issues.

Utilise Māori health frameworks.

Create a culturally and rainbow friendly environment.

Background

Takatāpui can be interpreted as 'intimate companion of the same sex’ and was most popularised in the love story of Tutanekai and Hinemoa. Today takatāpui has been reclaimed as an identity that encompasses all Māori who have various genders and sexualities, similar to the term LGBTQIA+. Takatāpui however, emphasises one’s gender and sexuality as being inseparable to their Māori identity and was reclaimed to challenge the traditional western idea of sexuality and gender that came with colonisation.

Takatāpui and Health care

Takatāpui people have unique issues due to their joint existence within two key minority groups. It is therefore important to highlight this population if we are to improve outcomes and reduce the burden of inequality in Aotearoa.

We know that being either LGBTQIA+ or Māori is associated with poorer health outcomes. Sadly, there is very limited data that directly assesses the effects of the intersectionality of the two. However, it may still be reasonable to assume that an individual who is takatāpui / both could experience even higher levels of discrimination, negative health experiences and poorer health outcomes than if they were just Māori or just LGBTQIA+.

-

Māori on average have the worst health status of any ethnic group in Aotearoa.

Māori life expectancy is considerably lower than non-Māori as well as having higher mortality at nearly all ages.

Māori have poorer outcomes across almost all chronic diseases including heart attack, stroke, diabetes and kidney disease.

Māori have higher rates of mental health issues, interpersonal violence and suicide.

Māori receive less access to, and through, high-quality health care services.

-

“The number of takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI survey participants reporting homelessness (19%) and ever exchanged sex for money or goods were high (28%). Homelessness was correlated to insufficient income and discrimination. Of those reporting ever engaged in sex work, of concern were the number reporting the streets and private settings as sites where sex was exchanged. On the face of it, data suggest a higher vulnerability to risk of sexual and physical violence and sexuality and gender-based discrimination when takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI-plus exchange sex on streets and in private settings rather than licensed brothels”.

“Discrimination experienced by takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI-plus survey participants – when using health and social services and on the streets and in public places – is grave, unacceptable, and induces unhealthy and at times life-threatening levels of distress. At 77%, takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI-plus people’s distress as a consequence of racism, homophobia and transphobia demands national and international action. High levels of discrimination, violence and abuse indicate that racism, homophobia and transphobia are entrenched, persistent and systemic in Aotearoa New Zealand. It should not be a surprise, then, that 45% of participants reported they were not open or only sometimes open about being takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI-plus. That takatāpui and Māori LGBTQI-plus people are unable to express their tuakiri (cultural, sexual and gender identities) and exercise their rangatiratanga or their Treaty of Waitangi self-determining rights for fear of violence, abuse is intolerable”.

“Survey participants reported the stress caused by society’s response to their cultural, sexual and gender identities contributed to self-harm and suicide. Fifty-five percent of survey participants reported they had ever contemplated self-harm or suicide, and 34% had ever self-harmed or attempted suicide. Moreover, support for those who had contemplated self-harm and suicide and those who had self-harmed and attempted suicide had largely come from friends and whānau if, in fact, any support was received”

-

Colonisation has had tragic effects on indigenous populations all around the world and Māori are no different. Cultural destruction, land loss, dehumanisation and racism have all impacted on the ability of Māori to thrive in their own lands. Despite clear evidence regarding these wider determinants of health, colonisation is often un-cited as a contributing factor and is still a contentious consideration in the broader sociopolitical context.

Colonisation has also caused a loss of connection to takatāpui whakapapa and culture. Māori oral traditions and stories demonstrate acceptance of a more fluid gender and sexuality before colonisation began, and the word takatāpui has its origins in historical Māori society. However, the loss of this history may have contributed to the loss of positive cultural, sexual and gender identity reassurance, as well as disruption of community and whānau support.

Māori health models of care

Health issues in Aotearoa are usually discussed using a Western heterosexual perspective. It is hoped that the promotion of Māori health frameworks will provide more culturally nuanced care. Modern health services may lack recognition of the role of the whānau (family/community), the inclusion of the wairua (spirit) and the balance of the hinengaro (mind) that are all as important o Māori as the physical presentation of disease. Models such as Te Whare Tapa Whā and Meihana take into account Māori specific research and draw on key cultural beliefs embedded in Te Ao Māori (the Māori world). These clinical assessment frameworks may assist health practitioners working with Māori patients and whānau to hopefully improve takatāpui health and reduce inequality. A key difference with these models is that they encourage the health provider to look at individuals from holistic and cultural perspectives. They include multiple contributors to health including physical, spiritual, mental, social, environmental and also the cultural or personal views of the individual. It is important to note that these considerations may have been designed with Māori in mind but can be utilised for any individual.

-

Te Whare Tapa Whā is the most popular Māori health model first established in 1984 by leading Māori health advocate Sir Mason Durie. The model is depicted as a whare (meeting house), which is made up of four taha (sides) representing: tinana, hinengaro, wairua, whānau. It is implied that only when all these things are in balance then we are truly healthy.

-

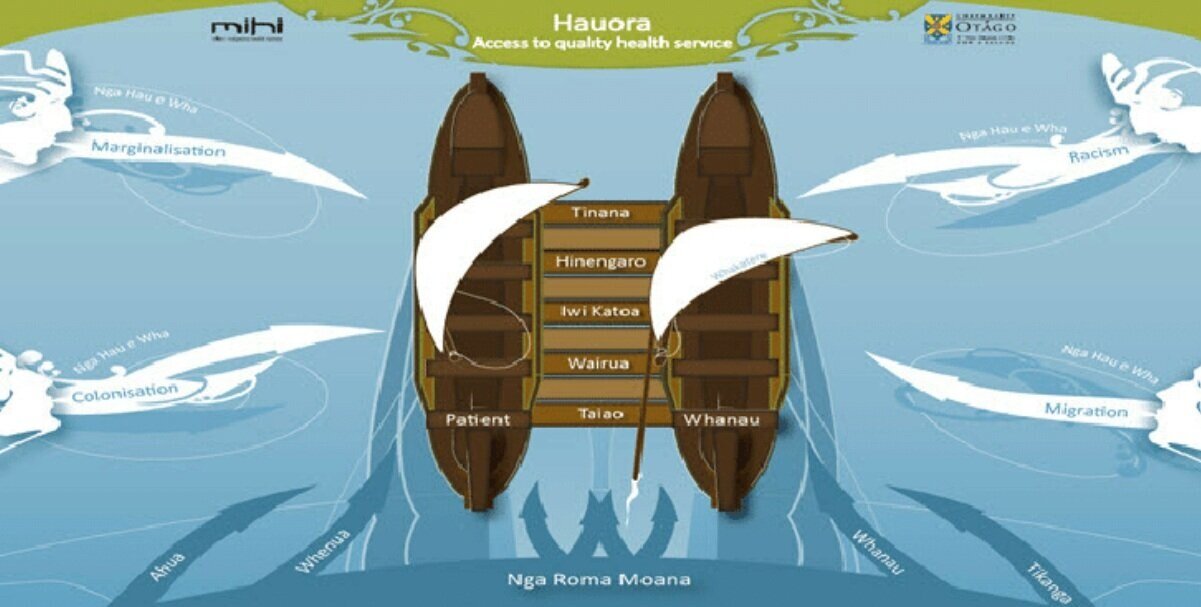

Description text goes hereThe Meihana model is an assessment tool containing 6 dimensions that are all interconnected and is typically depicted as a waka hourua (double-hulled canoe). It was initially created to facilitate the fusion of both clinical and cultural competencies in the mental health sector to better serve Māori who engage with the service. It does this by encompassing the strengths of the clinician while also encouraging them to explore the diverse needs of the client and their whānau. There are a few additional elements to the Te Whare Tapa Whā framework: taio (physical environment) and iwi katoa/ratonga hauora (support services). Additionally, the impact of Nga Hau e Wha (the four winds) of racism, marginalisation, migration and colonisation are considered within Māori health experiences and Nga Roma Moana (the ocean currents) acknowledge the influence of the individual’s involvement in Te Aō Maōri in their navigation of healthcare systems. This is also known as Māori beliefs, values and experiences (MBVEs) and is a general consideration to the whole process in an effort to avoid grouping all individuals into the same identical cultural care package. This can be exemplified by a patient who identifies as Māori but does not wish to be treated with a Māori cultural lens.

What can we do as health professionals?

-

Encourage the person to recognise their gender and/or diverse sexuality as being inextricably linked to their Māori whakapapa (genealogy)

A recent survey found that takatāpui had positive experiences and took comfort in exploring LGBTQIA+ identity in the context of Māori culture. This may help to reinforce both as being important and inseparable aspects of themselves.

Reinforce their takatāpui selfhood as being an acceptable pre-colonial identity

Refer to the love story of Tutanekai and Hinemoa and how within Māori, as well as Pasifika cultures there are a range of gender identities amongst ancestors

Where appropriate, re-connect their tinana (physical self) to their wairua (spiritual self) by facilitating their transition

Incorporate the wider whānau in their care to further instil resilience and strengthen their mana (self-pride. Another important finding in the survey was the importance of feeling supported by community and whānau which possibly led to a reduction in suicide rates by 50%.

-

A recent survey on the experiences and health of takatāpui showed some concerning results. Despite General Practitioners being the main point of contact within health for takatāpui individuals, only 9% reported their carer as being knowledgeable for their health needs as Māori and only 8% for their health needs as LGBTQIA+. Almost half of the surveyed group also were not sure if their health care provider knew their sexual identity or had not inquired about this, and a third reported their GP using uncomfortable terminology regarding their identity.

-

Visible cultural and rainbow friendly representation – flags, posters.

Please refer to our Rainbow 101 page for further suggestions.

-